Every year, millions of migratory birds embark on incredible journeys across North America. These travelers navigate vast distances, often covering thousands of miles to reach their seasonal destinations. With over 350 long-distance migratory species, the scale of this phenomenon is truly staggering.

Research from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology highlights key staging areas, such as Nebraska’s Platte River, where more than 500,000 Sandhill Cranes gather during their spring migration. Advanced tools like BirdCast radar tracking reveal astonishing numbers, with 378 million birds predicted in a single migration event.

These journeys are driven by the need to exploit seasonal food abundance and nesting opportunities. However, climate change is altering traditional routes and timing, posing challenges for these resilient travelers. Understanding the four major flyways—Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific—provides insight into the superhighways these birds use.

Key Takeaways

- Over 350 long-distance migratory species travel across North America.

- Nebraska’s Platte River hosts 500,000+ Sandhill Cranes during spring.

- BirdCast radar tracks 378 million birds in a single migration event.

- Climate change impacts migration routes and timing.

- Four major flyways serve as avian superhighways.

The Science Behind Bird Migration Patterns

Seasonal movements across continents reveal nature’s intricate design. These journeys are driven by a need to find food, escape harsh weather, and secure safe breeding grounds. Over millions of years, species have evolved to undertake these incredible travels.

Why Do Birds Migrate?

The primary reason for these journeys is survival. In winter, many regions lack sufficient food sources, prompting species to move to warmer areas. Additionally, the abundance of insects and other resources in northern breeding grounds during summer makes these areas ideal for raising young.

Evolutionary studies show that tropical ancestors expanded northward to exploit seasonal insect booms. For example, over 650 insect species peak in timing, aligning perfectly with the arrival of migratory travelers.

Navigation is a complex process involving multiple senses. Travelers use star compasses, magnetic fields, and even olfactory maps to find their way. A protein in their eyes allows them to see Earth’s magnetic field, acting like a built-in GPS.

Homing pigeons, for instance, rely on their sense of smell to navigate. Young travelers making their first solo journey are guided by genetic programming, ensuring they reach their destination.

The Role of Genetics and Environmental Cues

Genetics play a crucial role in these journeys. Hormonal changes triggered by light-sensitive pineal glands prepare travelers for the long trip. This phenomenon, known as Zugunruhe, has been documented since the 1700s.

Environmental cues, such as day length and temperature, also influence timing. However, climate change is causing mismatches. For example, aquatic insects in Ithaca now peak before May 15, while later-nesting travelers arrive too late to benefit.

Exploring the Major Migration Routes

North America’s skies are crisscrossed by ancient pathways used by countless travelers. These routes, known as flyways, serve as vital corridors for seasonal journeys. They connect essential habitats across the continent, enabling many species to thrive. Understanding these pathways offers insight into the incredible resilience of nature.

The Atlantic Flyway: A Coastal Pathway

The Atlantic Flyway stretches along the eastern coast, offering a coastal route for many travelers. Key hotspots like Dry Tortugas National Park and Cape May attract species such as warblers. Delaware Bay is a critical stopover, where Red Knots consume over 400 horseshoe crab eggs daily to fuel their journey.

The Mississippi Flyway: Following the Rivers

This flyway follows the Mississippi River, providing a natural highway for species like Prothonotary Warblers and Canvasback ducks. The 80-mile stretch of the Platte River in Nebraska hosts over 500,000 Sandhill Cranes each spring, making it a vital staging area.

The Central and Pacific Flyways: Diverse Journeys

The Central Flyway, often called the “Duck Factory,” includes the Prairie Pothole Region, a key breeding ground. Meanwhile, the Pacific Flyway features the Great Salt Lake, a stopover for 10 million shorebirds. Western Tanagers travel an impressive 3,000 miles from Mexico to Canada along this route.

Technology like geolocators has revealed fascinating details, such as Townsend’s Warblers using the Aleutian route. Flyway overlaps, like those of Cerulean Warblers, highlight the complexity of these journeys. However, threats like habitat loss, with only 40% of the historic Platte River remaining, underscore the need for conservation efforts.

For more details on these migratory routes and patterns, explore this comprehensive guide.

Timing and Triggers of Bird Migration

The timing of seasonal journeys is shaped by a delicate balance of environmental cues. These cues include day length, temperature, and food availability. Each year, travelers respond to these signals to begin their incredible journeys.

Seasonal Changes and Zugunruhe

Seasonal shifts trigger a phenomenon known as Zugunruhe, or migratory restlessness. This behavior is driven by hormonal changes linked to daylight. For example, Purple Martins now start their journeys 1-2 days earlier each decade due to climate change.

Robins rely on warmth to begin their travels, while warblers use internal clocks. These differences highlight the complexity of timing in the natural world.

How Weather Influences Migration Timing

Weather plays a critical role in determining when travelers begin their journeys. Sudden changes, like a false spring, can disrupt timing. In 2012, a March heat wave followed by an April freeze caused significant losses among early migrants.

Short-distance travelers, such as Phoebes, adjust faster to weather shifts than long-distance species. This adaptability helps them survive in changing environments.

Differences in Adult and Juvenile Migration Patterns

Adults and juveniles often follow different strategies. Male Indigo Buntings arrive at breeding grounds four days before females. Meanwhile, young Arctic Terns face a 60% mortality rate during their first journey.

Radar data shows that nocturnal travelers peak between 2 AM and 6 AM. These patterns reveal the challenges faced by younger travelers as they navigate unfamiliar routes.

| Species | Timing Change | Region |

|---|---|---|

| Purple Martins | 1-2 days earlier per decade | North America |

| Wood Thrushes | 22 days earlier since 1960 | Eastern U.S. |

| Common Yellowthroats | Abundance shifts | Various regions |

For more insights into how timing influences migration, explore this detailed guide.

Challenges Faced by Migrating Birds

Navigating thousands of miles comes with significant risks and challenges. From physical exhaustion to environmental threats, these travelers face numerous obstacles on their way to seasonal destinations. Understanding these hurdles is key to protecting these incredible journeys.

Physical and Mental Stress of Long-Distance Travel

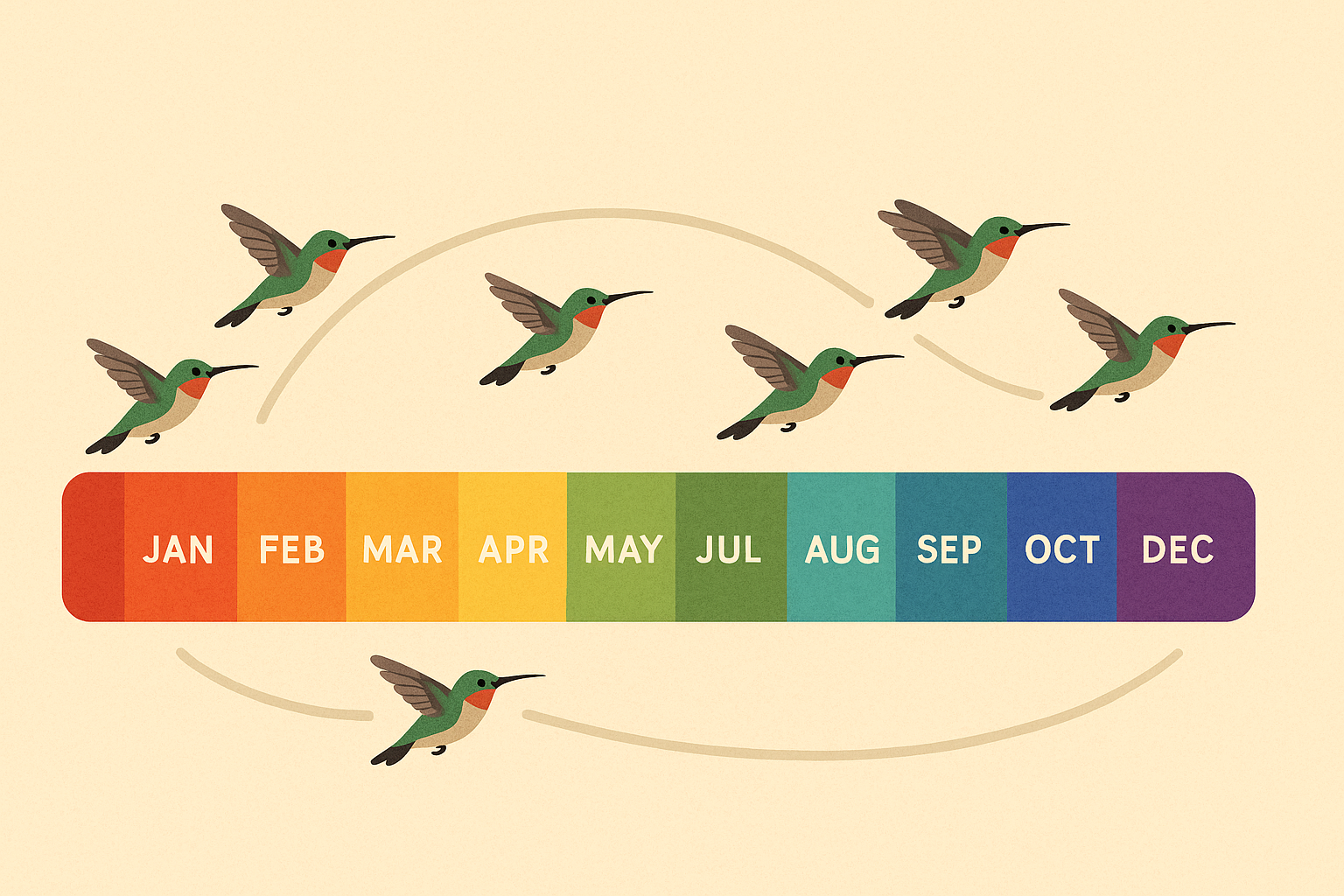

Traveling across continents demands immense energy. For example, the Ruby-throated Hummingbird crosses the Gulf of Mexico on just 2 grams of fat. Such journeys push species to their limits, often leaving them vulnerable to predators and exhaustion.

Mental stress also plays a role. Young travelers making their first journey rely on genetic programming, but mistakes can be costly. Radar studies show a 30% decline in nocturnal travelers since the 1970s, highlighting the growing challenges.

Threats from Human-Made Structures

Urban environments pose significant dangers. Collisions with buildings kill an estimated 600 million travelers annually in the U.S. alone. Window strikes account for over 1 billion deaths in North America each year.

Conservation efforts like BirdCast’s 3-day forecasts help reduce tower collisions. However, the rapid expansion of cities continues to threaten these journeys.

Impact of Climate Change on Migration

Climate change is altering the timing and routes of these travels. Phenological mismatches, such as oak defoliators peaking three weeks before chickadee fledging, disrupt food availability. Nutritional traps, like those faced by Thin-billed Murres during the DDT era, further complicate survival.

Radar studies reveal a 30% decline in nocturnal travelers since the 1970s. Citizen science platforms like eBird, with 1.5 million users, document shifting ranges, offering hope for adaptive conservation strategies.

| Challenge | Impact | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Building Collisions | 600 million deaths annually | BirdCast forecasts |

| Climate Change | Phenological mismatches | Citizen science monitoring |

| Urban Expansion | 1 billion+ window strikes | Conservation technology |

How We Can Help Protect Migrating Birds

Protecting the incredible journeys of migratory species requires collective effort. From creating safe habitats to reducing human-made threats, there are many ways to make a difference. Here’s how we can contribute to their survival.

Creating Safe Stopover Habitats

Safe habitats are essential for travelers to rest and refuel during their long journeys. Planting native species like oak trees, which host over 534 caterpillar species, provides vital food sources. Protecting areas like the Northern Prairie BirdScape, which safeguards 300,000 acres, ensures these species have the energy they need to continue their way.

Simple actions, such as maintaining green spaces and avoiding pesticide use, can also support these travelers. Every effort counts in preserving these critical habitats.

Reducing Light Pollution During Migration

Light pollution poses a significant threat, especially during nocturnal journeys. Programs like Lights Out in 33 U.S. cities have reduced skyscraper deaths by 90%, saving over 1.1 million travelers annually. Turning off unnecessary lights during peak migration periods can make a big difference.

Using window markers, like Feather Friendly solutions, can also reduce collisions by 85%. These small changes help ensure a safer journey for these species.

Supporting Conservation Efforts

Conservation organizations like the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Audubon are leading the way in protecting these travelers. The Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Act has funded over 700 projects, making a significant impact.

Citizen science initiatives, such as eBird’s Global Big Day, engage thousands of participants in tracking numbers and behaviors. Supporting these conservation efforts ensures a brighter future for these incredible species.

- Plant native species to provide essential food and shelter.

- Turn off lights during peak migration to reduce light pollution.

- Support organizations working to protect critical habitats.

Conclusion

The journeys of migratory species are a testament to nature’s resilience and adaptability. Arctic Terns, for instance, travel an astonishing 1.5 million miles in their lifetime, showcasing the incredible energy and determination required for these trips. However, the world is changing rapidly, with 3 billion travelers lost since 1970. This decline highlights the urgent need for conservation efforts.

Simple actions can make a big difference. Tools like the Bird Migration Explorer and local Audubon chapters empower individuals to contribute. Reducing collisions by 60% is achievable with measures like turning off lights during peak travel times. Dr. McGowan aptly notes, “These journeys aren’t just about movement—they’re the lifeblood connecting continents.”

By supporting these initiatives, we can help ensure these remarkable travelers continue to thrive for years to come. Together, we can protect the delicate balance of our natural world.

0 Comments