Blue Jays turn quiet yards into lively theaters. Their bright crest, bold stance, and sharp calls make them hard to miss. This introduction sets the stage for a Blue jay aggression case study that asks a common question: Why Blue Jays are Aggressive, and when are they simply protective?

Blue jays seem “aggressive” because they rely on intense territorial control and vigilant nest defense, especially during breeding season. Their sharp alarms and group mobbing quickly deter predators, while confident, high-energy resource defense makes them look dominant at feeders as they secure seeds and suet. Jays also use attention-grabbing calls—including occasional hawk mimicry—to clear space around food or family. What reads as bullying is really adaptive protective behavior and proactive risk management that helps a clever, social bird keep its young safe and its pantry stocked.

Across the Eastern United States and into Central Texas, Blue jay behavior stands out. Watch them guard feeders, dive-bomb pets, or rally the neighborhood with scolding calls. These moments reveal Blue jay territoriality, social bonds, and split-second decisions shaped by Corvid intelligence.

They are quick learners and crafty mimics. Blue jay mimicry includes hawk calls, and in captivity even cats’ meows or human words. Their choices often hinge on food and family. The Blue jay diet is mostly plant matter, yet they take insects and, on rare occasions, eggs or nestlings noted by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Their habit of caching acorns powers Seed dispersal by blue jays, reshaping forests over time.

This series blends field notes, peer sources, and backyard reports into a concise, readable guide. You will see how noise becomes strategy, how postures broadcast intent, and how bold birds manage risk. By the end, “aggressive” will feel less like a label and more like a toolkit for survival.

Key Takeaways

- Blue jay behavior often reflects protection of nests, mates, and food, not random hostility.

- Corvid intelligence drives fast learning, social signaling, and flexible problem-solving.

- Blue jay territoriality peaks near feeders and nest sites, specially in breeding season.

- Blue jay mimicry, including hawk calls, can warn allies or deter rivals.

- The Blue jay diet is mostly plant-based, with rare predation documented by major birding sources.

- Seed dispersal by blue jays through acorn caching shapes oak forests over long timescales.

Case Study Overview: Aggression, Personality, and Ecology of Blue Jays

Blue jays often spark debate at feeders and in parks. Yet, their behavior follows clear patterns. This study combines field notes with insights from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the Audubon Field Guide. It explores Blue jay personality, signals, and ecology, based on Corvid behavior research.

Scope and goals of this case study

The study focuses on territorial displays, alarm calls, mobbing, and rare predation. It also looks at cognition like mimicry and problem-solving. We compare these with magpies and other corvids to understand the patterns better.

It examines ecological roles, like acorn caching and seed dispersal. The goal is to distinguish between Protective behavior and aggression. We keep in mind the importance of Backyard birding and Conservation implications.

How “aggression” vs. “protection” is defined in bird behavior research

In this study, “aggression” refers to actions meant to exclude, intimidate, or harm rivals or threats. Examples include loud scolding, chasing, and occasional dive-bombing.

“Protection” focuses on guarding nests, mates, fledglings, feeders, and cached food. Researchers note crest cues—raised in arousal, lowered at rest—as real-time signals. This framing aligns with Corvid behavior research that weighs risk and reward.

Why this topic matters for backyard birders and conservation

For Backyard birding, knowing when Blue Jays are most assertive helps in placing feeders. Clear definitions prevent mistaking defensive displays for unnecessary hostility.

Conservation implications include recognizing how seed-caching supports reforestation and urban tree spread. Understanding Blue jay personality helps communities value their benefits while managing predation pressure.

Corvid Intelligence: The Smart Foundations Behind Bold Behavior

Blue jay intelligence is rooted in the Corvidae family, alongside crows and ravens. This family is known for memory, social learning, and adaptable behavior. These skills enable jays to navigate the challenges of their environment.

Blue jays within the Corvidae family alongside crows and ravens

Blue Jays, like American Crows and Common Ravens, are part of the Corvidae family. They cache food and remember where they hid it. They also adjust to new feeder setups, showing their problem-solving abilities.

Captive tool use and problem-solving: newspaper scooping and food access

In captivity, Blue Jays have been seen using newspaper to pull food closer. This shows their ability to plan and learn from mistakes. They also solve puzzles at feeders, proving they can change strategies when needed.

Such flexibility underlies quick choices in the yard, from testing a latch to finding a back route to a tray.

Mimicry as a cognitive signal: hawk calls, cats’ meows, and human speech

Blue Jays mimic a wide range of sounds. They are famous for imitating hawk calls, often at critical moments. Some have even mimicked cats and humans, showing their advanced vocal learning.

These abilities—memory, tool use, and mimicry—contribute to their bold behavior and quick reactions to threats.

Signals and Social Communication That Escalate or Defuse Conflict

Blue jays use fast, visual, and vocal cues in every meeting. Field observers from Cornell Lab of Ornithology say small changes in posture and voice can change a scene. A raised crest and loud calls can either calm or stir a crowd.

Crest position as a real-time indicator of alertness and arousal

The crest shows a bird’s mood. An upturned crest means alertness or worry. During threats, like a hawk, the crest goes up with stiff body.

A lowered crest shows calm, like when feeding or tending young. This helps birds understand each other’s feelings.

Pay attention to the crest’s movement. A quick raise shows curiosity, while a steady crest might mean a chase. In mixed flocks, these signals help avoid fights.

Unique facial and neck band patterns for individual recognition

Each bird has unique black banding around its face and neck. These patterns help birds recognize each other. They remember past interactions and know who’s who.

This recognition helps birds work together. They respond faster to calls and share duties. This leads to fewer misunderstandings and better defense against threats.

Group alarm calls and mobbing behavior against perceived threats

When a predator shows up, blue jays sound the alarm. Their loud calls bring in more birds. Together, they chase away threats like hawks or cats.

The loudness and speed of the calls matter. Short, sharp sounds get everyone’s attention. Fast strings of calls mean it’s time to act. Blue jays are loud and direct, perfect for quick action in busy areas.

Territoriality at Feeders and Nests

Blue jays show their territorial side where food and shelter are. In busy yards, they use loud calls and quick chases to keep others away. This behavior is clear to birds, pets, and people nearby.

Defending high-value resources: feeders, nest trees, and prime perches

At feeders, jays show off with raised crests and flared tails. They may hold a spot while others wait. Quick movements and wing flicks keep smaller birds from the best spots.

Near nests, jays defend a wider area. They fly fast and scold loudly to warn off intruders. When food is scarce, even bigger birds will back down.

Seasonal peaks: why nesting season intensifies confrontations

In spring, when eggs and nestlings need care, aggression peaks. Pairs take turns watching the yard with fast patrols. Raised crests and quick calls mean they’re serious about their territory.

During fledging, chases and block-and-hold tactics increase. This bluster is actually timed to keep intruders away from the nest.

Backyard case observations: dive-bombing and loud scolding

In cities like Houston and Atlanta, jays dive-bomb to defend nests. Quick passes and sharp scolds keep people and pets away. This happens most at dawn and late afternoon.

Compared to magpies, jays use more obvious calls and straight rushes. A calm approach and some space usually resolve the issue.

| Context | Typical Jay Response | Primary Cue | Observed Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Backyard feeder crowding | Feeder dominance with short chases | Crest up, wing flicks, harsh “jay” notes | Small birds yield perch; feeding resumes in turns |

| Nest tree perimeter | Nest defense blue jays with direct approaches | Rapid scolding, low passes, tail flare | Intruders retreat beyond canopy edge |

| Human path near fledglings | Dive-bombing birds without contact | Repeated warning calls and fast flyovers | People alter route; activity declines within minutes |

| Peak spring competition | Seasonal aggression birds escalates patrols | Frequent circuits of yard and fence line | Reduced intrusions and shorter disputes |

Diet Realities: Omnivory, Rare Predation, and Seed Dispersal

Blue jays have a clever way of eating. They forage in woods, suburbs, and parks. Their diet changes with the seasons, adapting to what’s available.

Typical diet balance: mostly plant matter, some animal protein

Mostly, Blue jays eat plants. They love acorns, beechnuts, seeds, and fruits. But they also eat beetles, caterpillars, spiders, and sometimes small animals.

These birds are flexible. They eat from feeders and then forage on the ground. This helps them stay fed during hard times.

Rare but real: egg and nestling predation rates and context

Blue jays sometimes eat eggs and nestlings. But it’s not common. Most birds don’t raid nests, and those that do act quickly.

When they do, it’s often because of food scarcity. They might fly off with a small carcass. These events are rare and usually happen in specific situations.

Acorn caching and accidental reforestation after the last ice age

Blue jays bury acorns far from the trees. They forget some, which sprout into new trees. This helps oaks spread across the forest.

Scientists think this behavior helped oaks grow after the ice age. One acorn at a time, jays helped new trees grow in sunny spots.

Unusual items like paint chips for calcium

Blue jays sometimes eat old paint. They need calcium for egg-laying. When they can’t find enough, they eat unusual things.

Putting out clean eggshells or oyster shells helps. It gives them what they need without harming homes. It’s a simple way to support breeding pairs.

Why Blue Jays are Aggressive

Blue Jays act aggressively to survive. In areas with hawks, snakes, and other birds, they use bold signals to scare threats away. This Adaptive aggression helps them make quick decisions and work together under pressure.

In parks and yards across the Eastern United States and Central Texas, these behaviors are common. They shape how people interact with wildlife. In suburbs, Suburban bird behavior is louder and more visible because of food and perches in small areas.

Adaptive benefits: protecting young, mates, and food caches

Jays use alarm calls, mobbing, and short dive-bombs to defend their nests. They aim to keep eggs, nestlings, and mates safe while protecting cached food. Social smarts and individual recognition help them coordinate without wasting energy.

Hawk-call mimicry is a quick, low-cost way to deter threats. A strong bluff can scatter competitors and give them time, even when a predator is watching. This bold approach explains Why Blue Jays are Aggressive during peak nesting weeks.

Risk–reward in bold strategies compared with quieter species

Compared to sparrows or chickadees, jays use visible warnings first. Their noise and crest-up posture raise the threat level quickly, ending trouble early. While there are energy costs and minor injury risks, the benefits often outweigh them.

By using signals before strikes, jays reduce the risk of close contact with predators. Their clear displays act as a shield, not a dare, fitting places where danger moves fast.

Human proximity amplifiers: feeders, pets, and suburban edges

Feeders concentrate calories, leading to more competition and scolding. Pets, like free-roaming cats, and foot traffic near nest trees trigger quick guard responses. These flashpoints shape Human–wildlife interactions every spring and summer.

On cul-de-sacs and at forest edges, Suburban bird behavior is more intense. Doorstep activity, lawn work, and dog walks add pressure, making Why Blue Jays are Aggressive more visible to those watching from a porch or path.

| Behavior | Main Trigger | Primary Goal | Common Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loud scolding calls | Predator sighting or human approach | Alert flock and deter threat | Yards, parks, feeder stations |

| Mobbing flights | Perched owl or hawk nearby | Push predator to relocate | Edge woods and tall street trees |

| Hawk-call mimicry | Competitor at food or nest zone | Low-cost warning or bluff | Feeders, cache sites, nest stands |

| Dive-bombing passes | Direct approach to nest | Immediate nest protection | Breeding territories near homes |

| Crest-raised posture | Heightened arousal under threat | Signal readiness to act | Suburban routes and trails |

Mimicry, Deception, and Defense

Blue jays use sound as a strategy. Their voices affect how birds react, how feeders are used, and how predators assess danger. Researchers find Blue jay hawk-call mimicry in parks and neighborhoods. This places them at the heart of Community bird dynamics, driven by bold Corvid vocal behavior and flexible Anti-predator strategies.

Hawk-call mimicry: warning or deterrence?

Recordings show jays mimicking Red-tailed Hawk and Broad-winged Hawk cries with great accuracy. Two theories exist. One suggests the call warns fellow jays of a raptor’s presence. The other proposes it’s a trick to scatter smaller birds, clearing space at feeders.

Either way, the call has an impact. Blue jay hawk-call mimicry can cause a brief pause, then movement. This pause allows for seed grabbing or regrouping. Field notes also show the same sharp call can draw other jays closer, creating a louder front against predators.

How mimicry influences neighborhood bird dynamics

A single hawk cry can change the pecking order. Finches, chickadees, and sparrows may seek cover, while jays feed. These moments reflect Community bird dynamics shaped by sound, presence, and timing.

When a real raptor appears, mass scolding and chase flights can follow. Group alarms recruit allies, and the chorus often pushes the predator off a perch. This pattern shows Corvid vocal behavior as social glue and tactical shield.

Comparisons to magpies and other corvid vocal strategies

European Magpies use rapid chatter, rattles, and varied squeals more than raptor-specific imitations. Jays, by contrast, focus on louder, sharper notes and hawk-like calls that project across yards and edge woods. In human settings, captive jays have even added cats’ meows and bits of speech, illustrating a toolkit that can flex for Anti-predator strategies or quick resource grabs.

Across corvids, flexibility is the theme. Deceptive signaling birds adapt to noise, buildings, and feeder routines, and Corvid vocal behavior scales from soft contact notes to forceful alarms. The outcome is a living soundscape where Blue jay hawk-call mimicry helps script who feeds, who flees, and who stands guard.

| Species/Group | Typical Vocal Focus | Role in Anti-Predator Strategies | Effect on Community Bird Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata) | Hawk-call imitations, loud jeers, sharp alarms | Signals danger, may deter rivals, recruits allies for mobbing | Momentary feeder resets; smaller birds scatter, then reassemble |

| European Magpie (Pica pica) | Complex chatter, rattles, modulated scolds | Broad alert system, less raptor-specific mimicry | Sustained neighborhood vigilance with gradual crowd response |

| American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos) | Caws in sequences, assembly calls | Strong mobbing coordination and predator tracking | Large-group pressure that can displace hawks and owls |

| Backyard Mixed Flock | Soft chips, contact calls, brief alarms | Quick cover-seeking behavior on sudden threats | Rapid dispersal and return cycles around corvid signals |

Regional Presence and Human Encounters in the United States

Blue jays are seen everywhere in the U.S., from road trips to quiet mornings. Their bright crests and loud calls are common in parks and neighborhoods. This makes them easy to spot, even for those who don’t bird watch much.

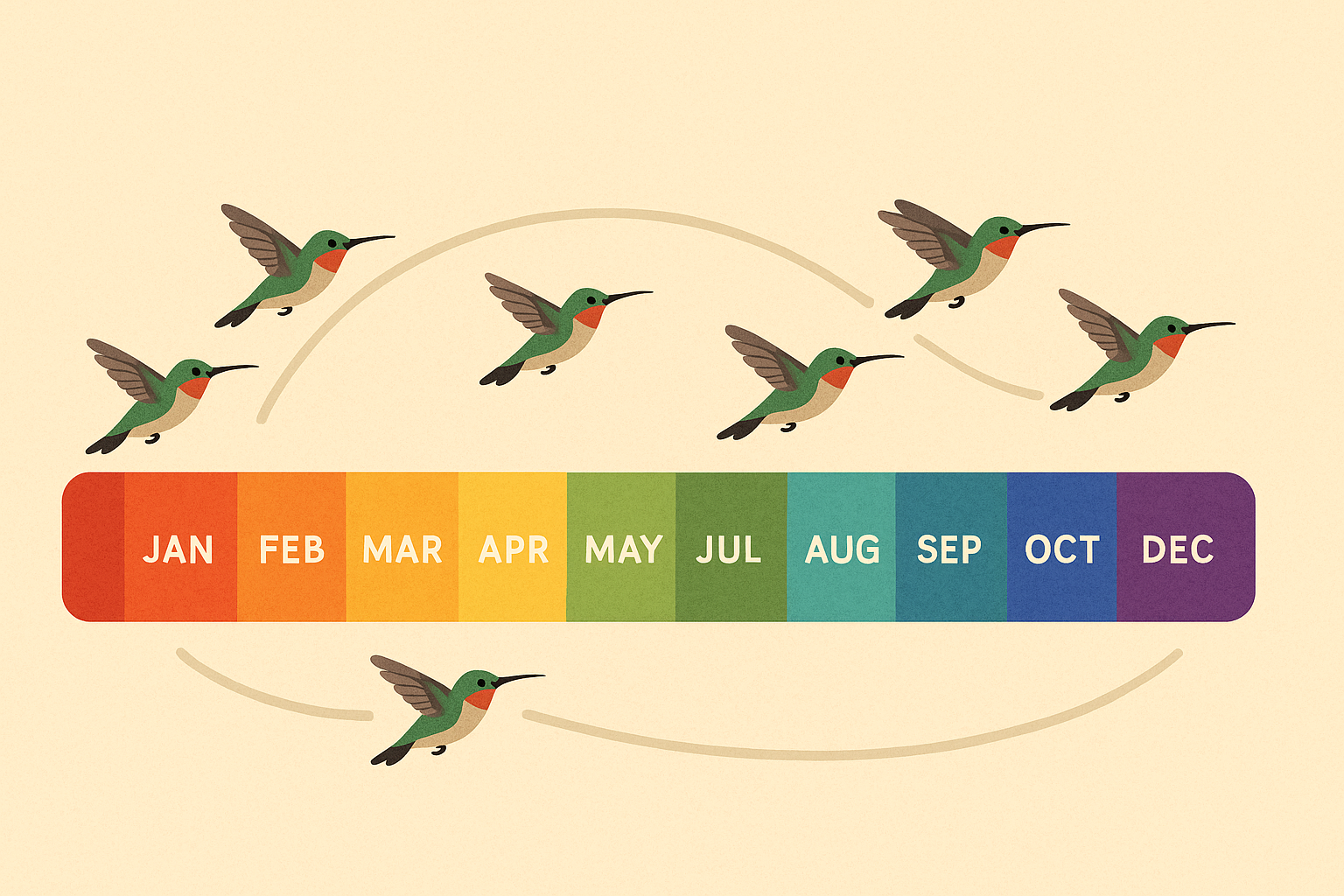

Ubiquity across the Eastern U.S. and parts of Central Texas

Blue jays are found all over the Eastern Seaboard, the Midwest, and the Great Lakes. They also live in Central Texas, from Austin to San Antonio. They like areas with mature oaks and mixed woodlots.

Every year, bird counts show many Blue jays in towns and state parks. They have food and shelter, so their numbers stay steady. Their movements change with the seasons, but they’re always around.

Urban and suburban adaptability: parks, yards, and forest edges

Blue jays are great at living in cities. They visit feeders, water features, and leaf litter for food. They also like forest edges, school courtyards, and city parks for perches.

In suburbs, they travel between lawns, street trees, and green spaces. The mix of hedges, fences, and roofs helps them move safely. This way, they can find food and protect their young.

Behavioral differences observers report across locales

Even though they’re the same everywhere, Blue jays behave differently in different places. Near homes and schools, they might be louder and more active. This is because of pets, leaf blowers, and traffic.

Compared to magpies in the West, Blue jays are louder and more noticeable. In busy neighborhoods, they dive-bomb quickly near nests and defend feeders fast.

| Locale | Common Habitats | Typical Human Encounter | Noted Behavior | SEO Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern U.S. suburbs | Parks, yards, forest edges | Feeder visits at dawn and late afternoon | Loud alarms, short chases, crest raised near pets | Blue jays in the United States; Suburban wildlife |

| Central Texas neighborhoods | Live oaks, greenbelts, riparian strips | Nest defense along trails and cul-de-sacs | Assertive scolding, quick mobbing in spring | Central Texas birds; Regional bird behavior |

| Urban cores | Street trees, courtyards, small plazas | Bold foraging around outdoor seating | High tolerance for people, opportunistic caching | Urban bird adaptation; Blue jays in the United States |

| Forest-edge towns | Mature hardwood edges, trails, picnic areas | Regular sightings along trailheads | Frequent sentinel calls, hawk-spotting alarms | Regional bird behavior; Suburban wildlife |

Conclusion

This summary shows a bold bird shaped by smarts, signals, and context. Jays use their crest height, facial bands, and sharp calls to communicate. They are very territorial, which explains their dive-bombing and scolding during spring.

Studies on captive jays reveal their intelligence. They use tools, solve problems, and even mimic other animals and humans. This intelligence is behind their confidence.

Diet research balances myths about jays. They mostly eat plants, with rare cases of eating eggs or nestlings. Their acorn caching helps spread oaks across the landscape. This shows how their actions impact the environment.

For household feeders, simple tips can keep peace. Spread stations apart, offer mixed foods, and keep pets away from nests. This reduces conflict for other birds too.

By understanding jays, we can live better together. A clear summary of their aggression, along with insights into their behavior, turns noise into signal. It shows how to coexist better, from the Eastern U.S. to Central Texas.

0 Comments